In der Phoenix-Sendereihe „Meine Geschichte“ kommen Zeitzeugen zu Wort. Am Sonntag, dem 12. Januar 2003, wird um 11:45 Uhr die Folge „Meine Geschichte – Die Jalta-Konferenz. Hugh Lunghi, der Dolmetscher Churchills“ ausgestrahlt.

Am 4. Februar 1945 trafen sich in Jalta auf der Krim Churchill, Roosevelt und Stalin. Die „Großen Drei“ suchten nach einem Weg zum Frieden und nach einer Weltordnung für die Nachkriegszeit. Noch waren sie Alliierte im Krieg gegen Deutschland, aber die unterschiedlichen Interessen und Gesellschaftssysteme waren bereits unübersehbar.

Der Grundstein für die Spaltung der Welt in zwei Lager wurde in Jalta gelegt: die Zerstückelung Deutschlands, die Westverschiebung Polens und die Neuordnung Jugoslawiens. Die Folgen: dem heißen folgt der Kalte Krieg. Aber noch waren die Großen Drei zur Zusammenarbeit bereit.

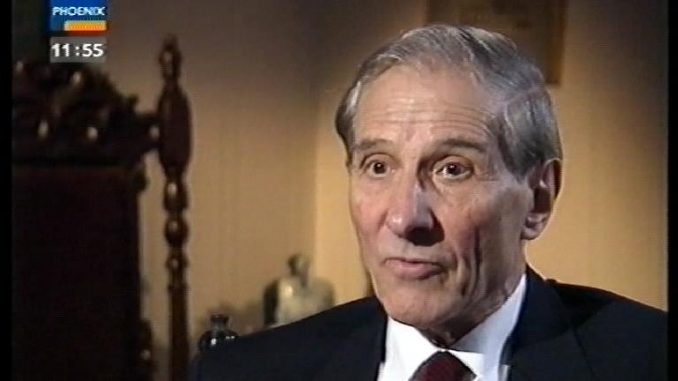

Hugh Lunghi (82) war als einer von Churchills Dolmetschern dabei. Seine Mutter hatte russische Vorfahren, so dass er Russisch als Muttersprache lernte. Mitte 1943 wurde er von der britischen Armee nach Moskau geschickt.

Lunghi hat die Konferenz von Jalta und ihre Vorbereitungen hautnah miterlebt. An vielen Beratungen hat er selbst teilgenommen. Neben persönlichen Erinnerungen und Anekdoten über die Gastfreundschaft der Russen und das Verhältnis der drei Staatsmänner untereinander berichtet Lunghi besonders über die politischen Ansichten Churchills. Der britische Premierminister trat für ein Nachkriegseuropa ohne sowjetische Dominanz ein und für ein faires Auftreten gegenüber der deutschen Bevölkerung.

Nach dem Krieg war Lunghi sechs Jahre als Diplomat und Chefdolmetscher an der Britischen Botschaft in Moskau tätig. Später ging er zum BBC World Service, wo er vor allem für Osteuropa zuständig war. Seit seiner Pensionierung ist er weiterhin publizistisch aktiv.

In einem Interview für eine BBC-Sendereihe beschrieb er seine Dolmetschertätigkeit einmal wie folgt:

I learned Russian at my mother’s knee. She was Anglo-Russian. And this resulted in my finding myself at three of the most historic occasions of the century, perhaps – when I was interpreting for the British side for Churchill and others at the Tehran Conference, the Yalta Conference, the Potsdam Conference. The Conferences of the so-called Big Three during the War, they were called.

I was in the army. But I was pulled out of my job as an artillery officer. And I was sent to Russia as aide-de-camp to the head of the military mission. It was he who ordered me to accompany him to Tehran. I didn’t know what I was going to do exactly, apart from interpreting for him, for my General. But in fact, when I got there, without any warning at all, I was not only interpreting for the British Chiefs of Staff, but I was told I would have to interpret for the Prime Minister and our Commander-in-Chief, Winston Churchill, and for his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden. I wasn’t their chief interpreter, but I had to stand in when the chief interpreter was otherwise engaged or resting.

The chiefs – that is, President Roosevelt of the United States, Stalin – Marshal Stalin, as he still was then – and Prime Minister Churchill – sat at a round table. Their advisers – that is, their foreign ministers and their military advisers – sat somewhat behind them. The interpreters sat slightly behind. The atmosphere was, on the whole, friendly. But there were moments of tension.

The three great leaders spoke in very different styles. For the interpreter, it does make a lot of difference. Stalin was very economical with his words – very precise. He seemed to know exactly what he was talking about – in absolute command of his facts, But very quiet. And it was very difficult to catch Stalin’s words, because of this mumbling, rather quiet, modest way of speaking, if you like.

President Roosevelt, on the other hand, I think was inclined rather to ramble, and would go on rather longer than his interpreter, I think, would have liked him to. Churchill’s language was the language of an orator. He prepared what he said very carefully. But very often, as we used to say – that is, the interpreters – you could almost see the right phrase sort of rumbling inside his brain and slowly coming down to his tongue, to his mouth. And then he’d come out with this wonderful phrase, which would hold you spellbound for a moment – and then you realised you would have to do your best to interpret this marvellous phrase. And of course, you never lived up to it properly.

But, after all, we used to say that an interpreter was rather like a concert artist – and his object was to get over the meaning, the tone of the score. And of course, as a result, you had to think of your interpreting as a performance. You were performing. You’re not there like a translating machine. You can’t be just a translating machine.

I was, of course, anxious about being accurate and therefore not making a mistake. However, once you start the interpreting, you get so caught up in trying to put it over properly, and you become a participant. So the worry goes, strangely enough. You’re not conscious at all. At least, I wasn’t at all. Perhaps it was because I was young – I was only 23 at the time. The arrogance of youth, and so on – you think you can get through it.

And I suppose I did make mistakes. But they didn’t lead to any disasters or crises. I assume most of the interpreters made mistakes. They were sorted out in the wash afterwards, so it didn’t really matter all that much.

Nachtrag

Hugh Lunghi starb am 14. März 2014 im Alter von 93 Jahren (03.08.1920 – 14.03.2014).

Richard Schneider